Now to Kant! And hopefully we’ll be able to tie the previous thoughts on liminality into this Kant reading. The main reading I’ve selected is an extremely famous section from Kant’s text Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (1783). Kant wrote this text as a clarification and response to critics of Critique of Pure Reason, but in many ways it had the opposite effect, serving to further complicate the first Critique. For this reason the Prolegomena stands as a text on its own. It’s enormously interesting although not as studied as it should be in the scholarship.

Generally speaking, the text approaches the problem of the first Critique through the lens of metaphysics and three iterations of the “transcendental question”: the first iteration asks “how is pure mathematics possible?”; the second asks “how is pure natural science possible?”; and the third asks “how is metaphysics in general possible?”. Our reading, the section on the limit entitled Determining the Bounds of Pure Reason, takes place at the end of this third question and directly precedes perhaps the most important (but somewhat secret) chapter of the book, which iterates the transcendental question for a fourth time and perhaps could be considered the highest, ultimate and the last iteration of the transcendental question, namely, “how is metaphysics possible as a science?”

The paragraphs on the limit appear on the border between the question of how metaphysics in general is possible and the question of how it is possible as a science. Just to reiterate: the section on the limit takes place on the border demarcating metaphysics in general and metaphysics as a science. We might even go so far as to say that the paragraphs about the limit take place on the limit of the question of metaphysics, textually at that precise moment where its systematicity is questioned. And when we turn to the German we see that the text isn’t separated by a huge blank space on the page. Rather, the end of §60 doesn’t lead into §61, but instead gives way to a Auflösung, a (re)solution, without any indication that an entirely new section has been started (as it is in the English translation).

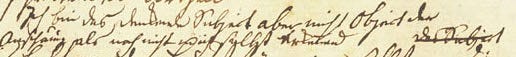

It’s a very minor point but it hints at the performativity that is always at work in Kant and that one has to keep an eye out for. One can find traces of this throughout Kant’s corpus. Let me give you another example of this: at one point in a fragment from Opus postumum Kant talks about the ungraspability of the I, that there is something we can’t quite grasp about the I. But in the second part of this fragment he “accidentally” leaves the word Ich out of the sentence. So right where he claims that one cannot know oneself as an object called “I”, he says, and I translate it loosely here, “I am the thinking subject but not object of intuition as still do not know myself” (OP 22:91, my translation).1

Can you see what’s missing? It’s the second “I”, since it should read something like “I am the thinking subject but not object of intuition as I still do not know myself” or perhaps “I am the thinking subject but not object of intuition as still I do not know myself”. Either way, it’s a grammatical, textual error but there’s an (inadvertent) enactment going on, as though Kant’s mistake points to the very idea he’s trying to express, namely, that I cannot know myself as an object called “I”, that this “I” as object is technically absent. There are two layers depicting the same scenario but in two distinct ways: one layer is the content of what Kant is saying, the other is the form of how he says it.

One finds instances like this throughout Kant’s work both published and unpublished. Just another very easy, low-hanging example is the partial deletion of the transcendental object in the second edition Critique of Pure Reason. If there were any concept most fitting for partial deletion in the first Critique then it is certainly “transcendental object”, which designates a ghostly “something” both present and absent; both there and not-there.

Here in the Prolegomena it is no different in terms of performativity. Right on the frontier between the question of the possibility of metaphysics in general and metaphysics as a science is a discussion about what a limit is.

Now, getting into the substance of the text, I’m going to start by immediately giving the whole gambit of my reading of this Kant section away. To this end of giving the game away I quote two lines taken from Geoffrey Bennington’s book, Kant on the Frontier, which serve to frame everything I’m going to discuss:

First quote: “on one side of the Grenze [reason] is merely understanding and on the other it is Schwärmerei and fiction” (Bennington, Kant on the Frontier, p.219).

Second quote: “The attempt to trace a secure and definitive frontier between Schranke and Grenze is doomed to fail” (Bennington, Kant on the Frontier, p.222).

I ask you to keep these two moments in mind as we go and treat them like anchoring points throughout the following.

Just to briefly unpack these two quotations. First: the Grenzen—translated as “boundaries” in the standard English Kant translation to distinguish it from Schranken, which is translated as “limits”2—mark two sides of reason: pure concepts of the understanding or the Transcendental Analytic on one side and the ideas of reason or the Transcendental Dialectic on the other.

Second: the answer to the question of whether the border between boundaries and limits is itself a boundary or a limit is inherently unanswerable, and calls for indefinite suspension.

So now I’ve given everything away in two lines but let’s go to the actual material to see this in action, so to speak.

First of all you’ll notice from the title of the section in Prolegomena (stretching from §§57-60) that this isn’t about the limit as much as about “determining the boundary”. Much of this section represents a labor to distinguish between a limit and a boundary, to tease apart their meanings so as to find where the line between them might be; it is a determining of the boundary by way of placing the boundary itself under question, one might say. The German for “determining the boundary” here is “Grenzbestimmung” so it’s all one word meaning boundary-determination or more simply, demarcation. So once translated a bit more literally the title would be more like “on the boundary-determination of pure reason” or perhaps more simply, “on the demarcation of pure reason”.

Now this “of”, which is der in German, is ambiguous as to whether it is a demarcation of, in the sense of by, pure reason or whether it’s a demarcation of, in the sense of on or to, pure reason—is it a demarcation that happens by reason or is it a demarcation that happens on or to reason? I think, again pointing to the performativity that we’ve just been discussing, this ambiguity isn’t one to be (re)solved but to be held taught: it is both a boundary drawn by pure reason on and to pure reason; pure reason determining its own Grenzen.

Immediately, then, it isn’t about limit at all but about boundaries. So we’re called upon to ask: what’s the difference?

The first line I want to unpack operates right on the edge of this difference. It’s on AA 4:351 (p.102 of the standard Cambridge translation), where Kant says:

Our principles, which limit the use of reason to possible experience alone, could accordingly themselves become transcendent and could pass off the limits of our reason for limits on the possibility of things themselves (for which Hume’s Dialogues can serve as an example), if a painstaking critique did not both guard the boundaries of our reason even with respect to its empirical use, and set a limit to its pretensions.

Now, we’re going to consult the German quite a bit here to unpack it, and we’re going to go slow, picking apart this sentence to get a feel for the type of interrogation Kant is launching.

Firstly, the subject of the sentence is “our principles” and the principles he’s referring to here are Prinzipien, which means, provisionally, that they aren’t Grundsätze of the understanding, that is, the properly constitutive empirical principles that emerge after a category has been schematized. Although in a slightly ambiguous way (the limitation to objects of possible experience surely occurs through Grundsätze and not only Prinzipien?), we are dealing here with principles of reason instead of principles of the understanding. Or, to say the same thing more bluntly, we are in the world of the Transcendental Dialectic and not the world of the Transcendental Analytic, although we have to refrain from deciding on this conclusively at this early stage precisely because it may turn out that we are in neither of them, that we are between them, so to speak.

The next part of the sentence refers to einschränken, which the translation puts in as “limit” in the sense of the verb “to limit”. Einschränken and Schranke, this is where we find our concept of limit in Kant. But einschränken in this context also means something like limiting in the sense of restricting or narrowing down or, to play on the way this sounds to an English speaker’s ear it has the vibe of shrinking in the sense of shrink-wrapping which surrounds something and restricts it or binds around it. So we might very freely and again non-conclusively translate the type of action this limit has in the sentence like this: “our principles (of reason) shrink the use of reason to mere objects of possible experience” or, “our principles (of reason) shrink-wrap the use of reason around mere objects of possible experience.” And this means that reason is tethered to the realm of objects of possible experience so that it doesn’t fly off into fancy, into Schwärmerei, which means fanaticism and dogmatism.

The next part of the sentence that we come to: these principles which have shrink-wrapped the use of reason around objects of possible experience, may become transcendent by passing-off or giving-out (the German is ausgeben) the limits of reason for/in place of the limits of things themselves. Note that this “things themselves” isn’t “things in themselves” but rather “Dinge selbst”. To rephrase Kant’s point, these principles which have been restricted by the labor carried out in the first Critique nonetheless still have a tendency to fly off the rails, to mistake their shrinking to objects of possible experience for a shrinking of the things themselves entirely divorced from the activity of reason. I think another way of putting this is: the purely subjective limit of reason (by, on and to reason) has a tendency to be mistaken for an objective limit of things themselves.

And this takes us to the next part of the sentence: the painstaking, meticulous, careful (the German is sorgfaltig, so it has a deep connection to Sorge, which is care, concern or worry—something that will no doubt prick up the ears of Heidegger readers) critique guards the Grenze of our reason in view of its empirical use. Guarded in the German is bewachte and can mean more literally watched—wachen in German—to keep a close eye on such and such. So without the critique keeping a close eye on but also setting/positing (the end of the clause in the German is setzte) the Grenze of reason with respect to empirical use, a move towards transcending the Schranken, the limits, would occur. So it’s a strange thing that’s going on here, almost like a nesting of boundaries and limits and indeed this idea of limits nested in boundaries is precisely what Kant is preparing us for.

We might say that the protective shell of the limit, the limit of the limit, that which holds the Schranke together and stops it from being transgressed is none other than the boundary of reason, the Grenze. Or put more simply and to bring out the nesting: the Grenze is the limit of the Schranke. But then we have to ask, is this a true limit or is it a boundary and where are we actually placing the difference between them? Is it really a boundary that shrinks around the limit or vice versa?

Already we can tease this type of thought out from Kant’s opening words and it’s a question that Kant is clearly asking himself. So before we go further into the implications of this question and join Kant in laying out the differences between limits and boundaries, it’s important to see where the need for such a distinction comes from from a wider perspective within the critical philosophy. In fact, it’s quite easy to diagnose why it’s so important to Kant based on this section. The issue is satisfaction, which in German is Befriedigung, a word that somewhat constellates with the word Vollendung, that is, completion, or more literally, full-ending. Befriedigung refers to satisfaction in an ending. For example, the ending of a film that neatly resolves itself without leaving us with a cliffhanger. There’s also an element of loosening up with Befriedigung which, although they are different words, reminds us that if we swap two letters around we get Befreiung, “deliverance” or the verb, befreien which means to liberate or to free. So there’s a problem with satisfaction, with deliverance from and loosening up of all the entanglements reason tends to get itself into.

This is why the necessity of the Transcendental Dialectic in the first Critique is just as much a tendency as the Transcendental Analytic, for within critical philosophy there is a need to permit some sort of transgression of the bounds so as to partially quench reason’s desire for satisfaction even while maintaining that it may not transgress the limit. And so we are led to the need to rigorously distinguish between them. In Kant’s words on AA 4:352 (p.103), even after the boundaries of reason have been set reason still “searches for peace and satisfaction [Ruhe und Befriedigung]”. There is something dissatisfying to reason about being shrunk to objects of possible experience; it tends to attempt to move beyond this limitation regardless of the labor of critique. Indeed, there is something inherently deflationary and unsatisfying about sticking with the Transcendental Analytic side of critique, and this is what forces Kant to attempt to thicken the line between limits and boundaries on the boundary itself.

I go into much more detail about this moment in my book, Metaphysics of Nature and Failure in Kant’s Opus postumum, pp.136-138.

We’ll see there are many problems with maintaining these translations, but I try to stick to them here for simplicity. A nice pointer to this difficulty can be found in the fact that in English translations of Hegel everything is reversed. That is, Grenze is translated as “limit” and Schranke as “boundary”. Far from a “correct” and “incorrect” translation, however, I think it is this very problem of translation that brings out the need for a technical difference between them and, moreover, how difficult this proves to be, especially for Kant.